Yuken Teruya

‘The Big and the Small’

by Yuken Teruya

Photo: Hans-Georg Gaul, Berlin.

In a video series created in collaboration with the artist Linda Havenstein, a face appears in a wide shot, silently looking into the camera. Minimal facial expressions and traces of emotions stand out in the face; the person portrayed seems to be thinking about something. After a while the silence is broken and the person says “I’m sorry”. Fade-out. The next person appears, this time different gender, different skin color, and the person also seems affected thinking about something, then says »I’m sorry.”

I too can be seen, I too apologize. For all the injustice that is part of my history qua my nationality, for all the violence that I did not stop. An apology for all the people who are waiting for an apology. If a state is supposed to stand for the people of its citizenship, then by implication, maybe a citizen can apologize instead of the government?

The series is called The Apology and deals with the relationship between individual responsibility and broader social contexts. It inquires about the position of the individual in the larger context and the options for action that each person has in the face and knowledge of what is happening around them.

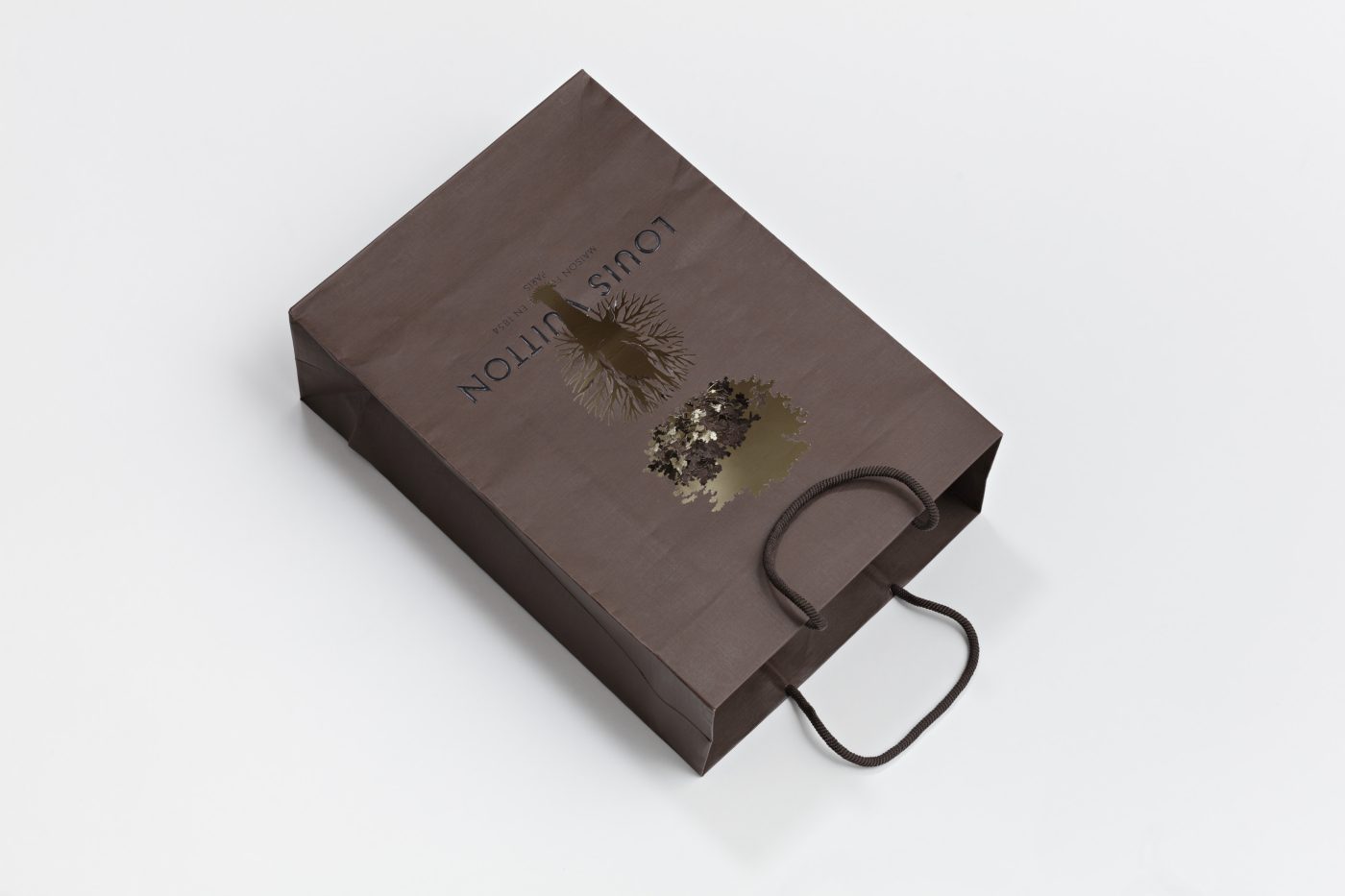

This tension between an individual and a seemingly overpowering group is something I also address in other works. In the Notice-Forest series, two apparent opposites face each other. The paper bag, a mass product that brings with it all the convenience of predictability and a comparability to the point of featurelessness, the speed with which it can be used and removed from consciousness, and a calculated transience of its existence. The bag denies a responsibility of the consumer, it soothes and lulls into its apparent insignificance. It whispers, “Don’t notice me, I’m nobody, I have no value.”

The tree, however, which opens up in the bag, brings with it the claim and the will of existence, it is there, although it should not be there at all. Not only is it a very concrete tree, modeled after individual plants from the urban spaces of the global metropolises, thus annihilating the supposed interchangeability of the bag, but it also inverts the production and life cycles of the mass product.

Through its existence it interrupts the predetermined life cycle of the disposable product, it not only refers to the tree that stood at the beginning of the bag, but through its existence it also prolongs its life in the now, at the same time its end will be different than it was predetermined. It intervenes, it forces attention, re-evaluation and consideration.

If there is something I want to bring to understanding (notice) with this work, it is that the bag in truth has never been featureless or worthless, that it has always been a living tree, and that the apparent ease achieved with the form of mass production and distribution has always been deceptive. What Hannah Arendt formulated for political contexts in the mid-20th century carries over at the beginning of the 21st century and in the face of the climate crisis to a multi-layered mishmash in which consumers are the agents of action.

We have never been absolved of responsibility for our actions, even if global production structures and consumer cultures invite us to do so. We have never had the right not to consider what we do. The little vulnerable paper tree thus hijacks the narrative of modern and convenient mass production, the passive consumer, and the assumption that an object is worthless if individuals receive it for free at the moment. For the supposed cost- and property-free mass production bag costs everyone dearly in the now and in the future.

Text: Yuken Teruya