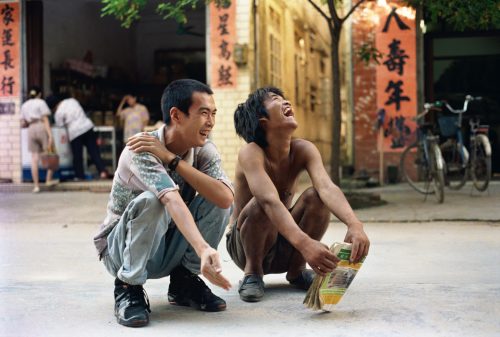

Cao Fei’s multifaceted and multimedia artwork is based on close observation and a critical, inquisitive attitude as regards her immediate surroundings. She begins with the everyday and mundane, the personal, the supposedly intimate. One of her reoccurring themes is the city and the living together in urban environments: From 2007 to 2010 she has created a complex, virtual city—RMB City—in the realms of Second Life and in 2013 Cao Fei conceived Haze and Fog, a new type of Zombie film set in modern China, and only last year she finished another film about a mythical post-apocalyptic metropolis, called La Town. These projects are related not only to Cao Fei’s principal examination of basic human conditions but also to a conceptual shift of perspective—a zoom from virtuality to a close-up of 21st century Beijing and back to an imaginary Sci-Fi view.

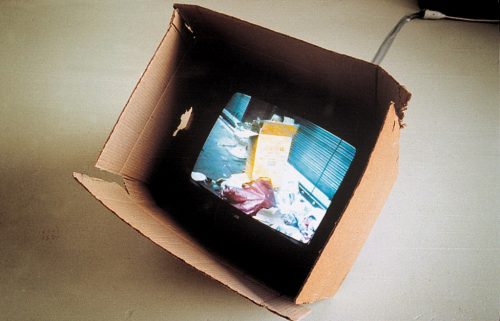

When we watch Cao Fei’s video La Town, she places us right in the midst of her images of an envisaged, incipient, recently past or threatening—perhaps we don’t know?—catastrophe. In the first section of the film, the camera, as it moves through the pitch-black streets of La Town, shows signs of destruction, but the human figures within the scenes appear unaffected. In the second part of the video, we see daylight, a playground, classical-looking fountain statues, a funfair. In the film’s third part, the camera roves through homes in an apartment block—a reference to Cao Fei’s film Haze and Fog. Here, the normality of ordinary everyday life prevails. Only in the final part does the scene acquire a mood of apocalyptic destruction: demonstrators, injured people, fire, sirens. Cao Fei takes the pleasant model railway world and uses it as the basis for a human community, a ‘world community’—reduced down to a miniature scale as La Town, where a happy coexistence is no more than a promise, a brief interlude in the unrelenting tide of a violent, destructive history. Her model adapts two other artworks with a spiritual affinity to her own ideas that have provided her with inspiration—the literary/filmic reflexive art of Duras/Resnais, and Italo Calvino’s model utopian cities. She transposes these artworks out of their original context in 20th-century Europe, and into our present-day globalized world. The search for authenticity (so often futile in reality), memory as the imparter of meaning, and the viability or otherwise of political and social utopias: all of these find a temporary place in the ‘Night Museum,’ the museum that Cao Fei takes us to visit in the film’s final sequence. When one considers that the policymakers of China are building thousands of new museums in an attempt to compensate the hundreds and thousands of people who work in the factories in China’s great cities, with their populations of millions, for the terrible fears with which their everyday lives are filled, one is uncertain whether the final image offered to us by Cao Fei is intended to be seen as a utopia, or as a manifestation of trauma.