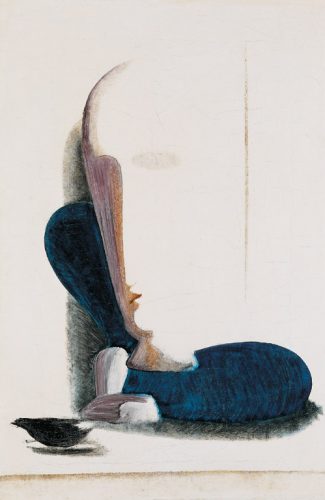

Oskar Schlemmer, a student of Adolf Hölzel in Stuttgart around 1910 and an outstanding lecturer at the Bauhaus, never saw the human being as a mere motif but always considered it as part of an all-encompassing reference system. For him, the human being was a cosmic creature, a world totality consisting of intellect, nature and soul. Via the development of his ‘differentiating human’, an artificial figure shortened in a stereotyped manner, and emphasizing the basic functional and proportional correlations, Schlemmer arrived at the ideal representation of the human figure. Schlemmer’s fight for the ‘expression’ he was seeking broke through with the reliefs started in 1919: these are no longer pictures in the familiar sense, but, as Schlemmer noted in 1919, “more like tablets […] that break through the frame to attach themselves to the wall and become part of a greater area, of a space that is greater than themselves, so that part of an intended, desired architecture is compressed in them, […] which would be the form and the law of their surroundings. In this sense: tablets of the law. Representing the human form will always be the artist’s great parable”. An example of such a tablet of the law is Relief H, 1919, in which the formal breakdown is intensified to become a formally abbreviated art-figure, and also integrated into three-dimensional surroundings and yet referring back to man as the model and measure of all things in the sense of the ‘pars pro toto’.

close

checkout*

Shopping cart

Versand und Abwicklung erfolgt über die Bücherbogen am Savignyplatz GmbH in Berlin. Für Fragen zu Bestellungen wenden Sie sich bitte direkt an info@buecherbogen.com

Handling and Shipping is done by theBücherbogen am Savignyplatz GmbH in Berlin. For questions regarding your order please contact info@buecherbogen.com directly.

*

Bestellungen aus der EU sind bei PayPal auch ohne Anmeldung möglich. Sie können dann auch bequem per Bankeinzug oder mit Ihrer Kreditkarte zahlen.

Für diese Option klicken Sie bitte auf PayPal und wählen anschließend die Bezahlung "Mit Lastschrift oder Kreditkarte" aus.

Buyers from within the EU can use PayPal even without having a PayPal account.

Via Paypal you can also check out with direct debit or with your credit card.

For this option please click on "Check out with PayPal" and make use of the "Payment by Direct Debit or Credit Card".